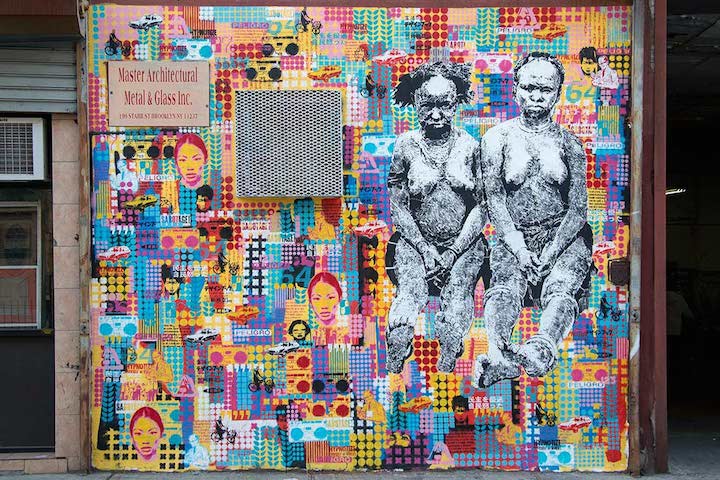

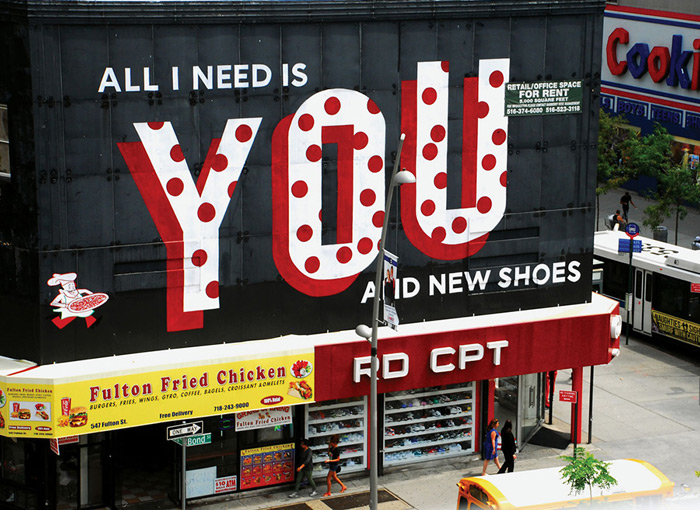

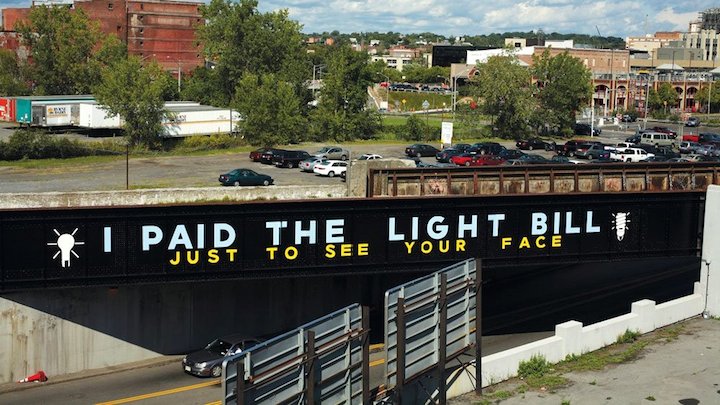

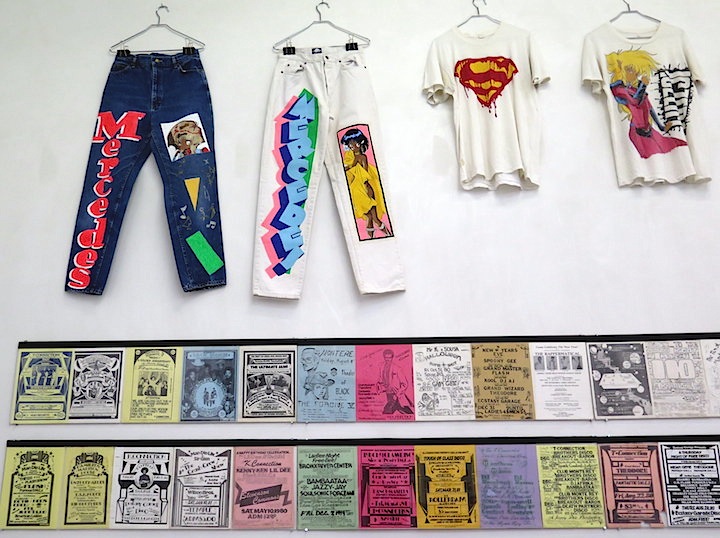

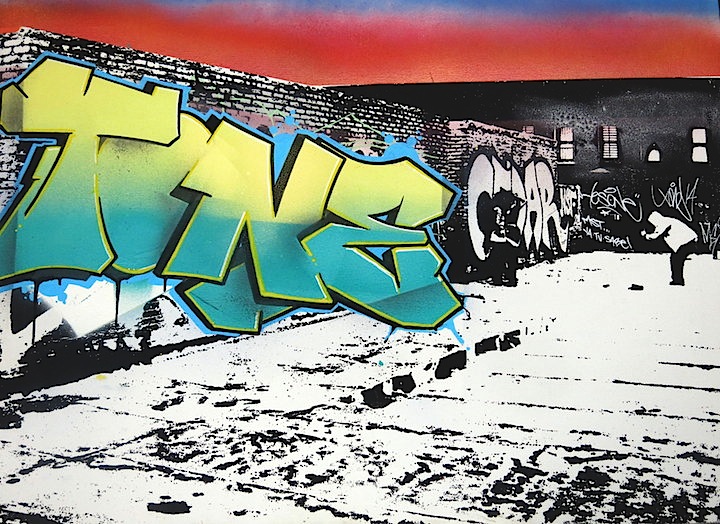

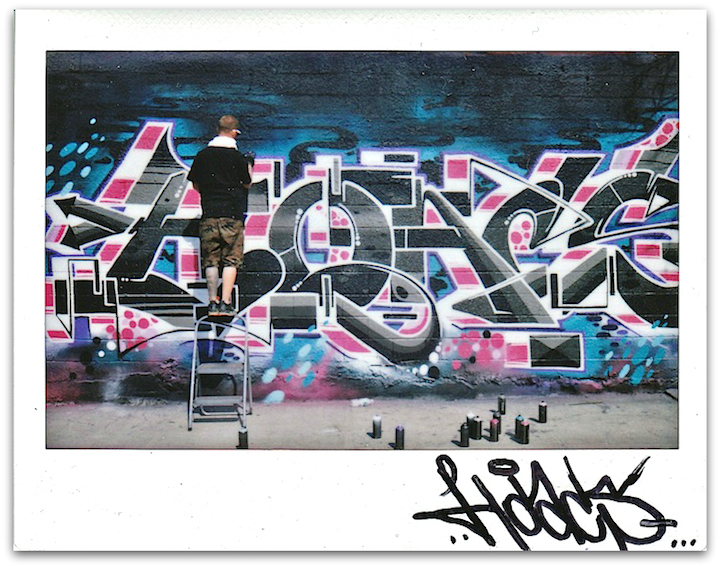

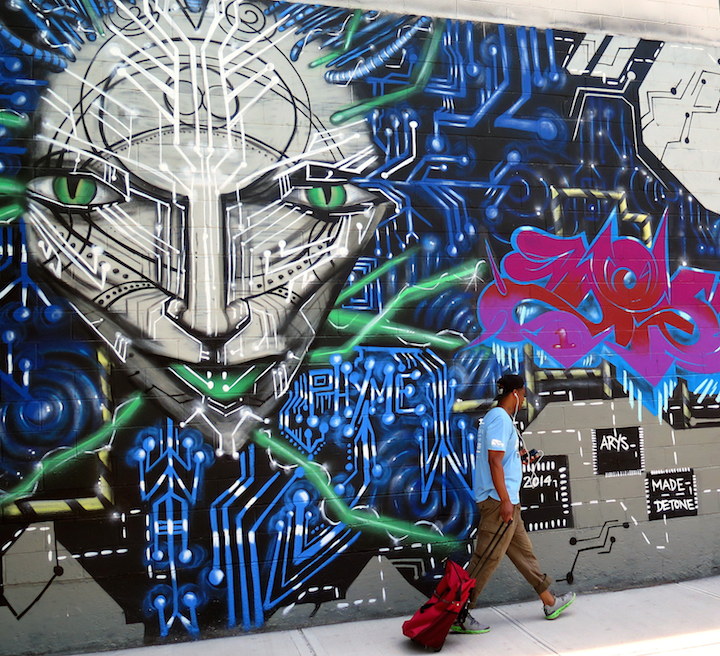

Bronx-based Sienide aka Sien is one of NYC’s most versatile artists. His delightful compositions — in a range of styles from masterful graffiti writing to soulful portraits — continue to grace public spaces throughout the boroughs. I recently had the opportunity to interview him:

When did you first get up?

I started tagging and bombing on the Grand Concourse in 1981 with my older brother. I was living at 176th street and Morris Ave. I did my first piece in 1985 with my then-bombing partner SEPH. Jean13 was also there, and he helped me shape up my letters. Ironically, my first piece was also a legal commission.

What was your preferred surface back then?

I really wanted to get into the yards. But I couldn’t, so I hit trailers instead. There was a great lot over in Castle Hill, where we painted and made a tree-house to store our supplies.

What inspired you to get up?

Everybody around me was writing.

Did you paint alone or with crews?

Both. In 1986 IZ the Wiz put me down with TMB after he saw my black book. Since, I’ve painted with the best of the best: OTB, FX, KD, GOD (Bronx) and GOD (Brooklyn), MTA, Ind’s, Ex-Vandals, XMEN, and TATS CRU

What about these days? Do you paint only legally?

Oh, yes! I’m too old to play around, and I want to get paid for what I do. I also want to paint in peace.

How did your family feel about what you were doing back in the day?

They weren’t happy. When I was arrested for motion tagging with my cousin on the 6 train, my uncle — who was my dad at the time — told me that no one would ever hire me because I defaced public property.

What percentage of your time is devoted to art?

At least 85% of it.

What is your main source of income these days?

It’s all art-related. I sell my work, earn commissions for painting murals and I also teach.

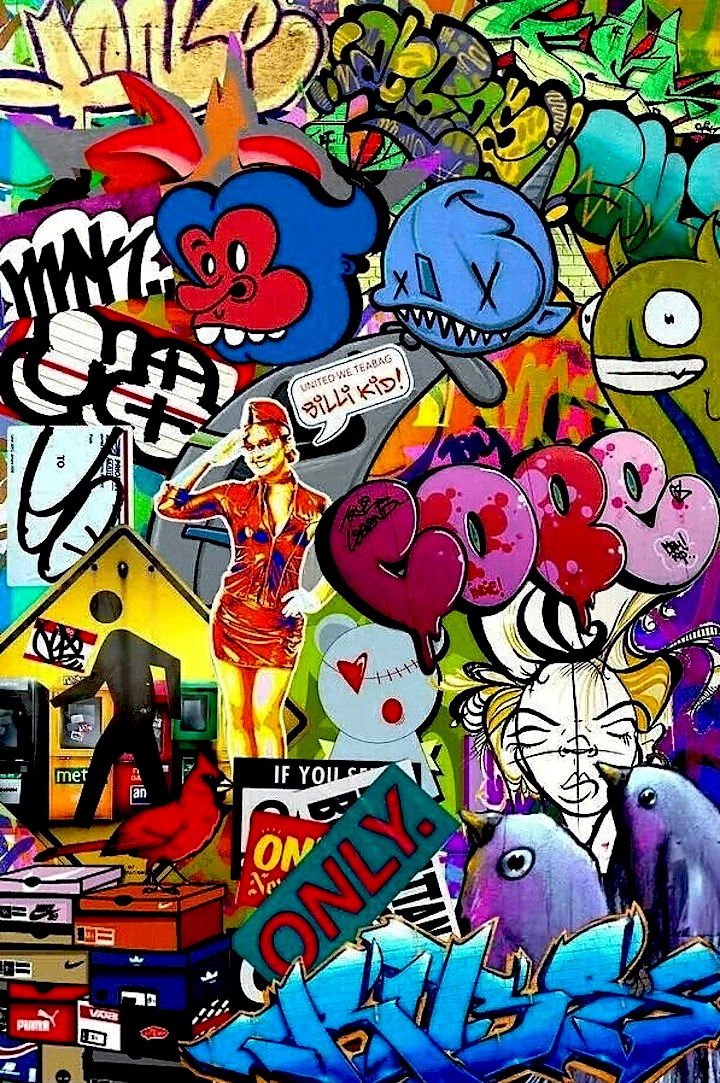

Have you any thoughts about the street art and graffiti divide?

I love them both. I have forever been trying to marry them.

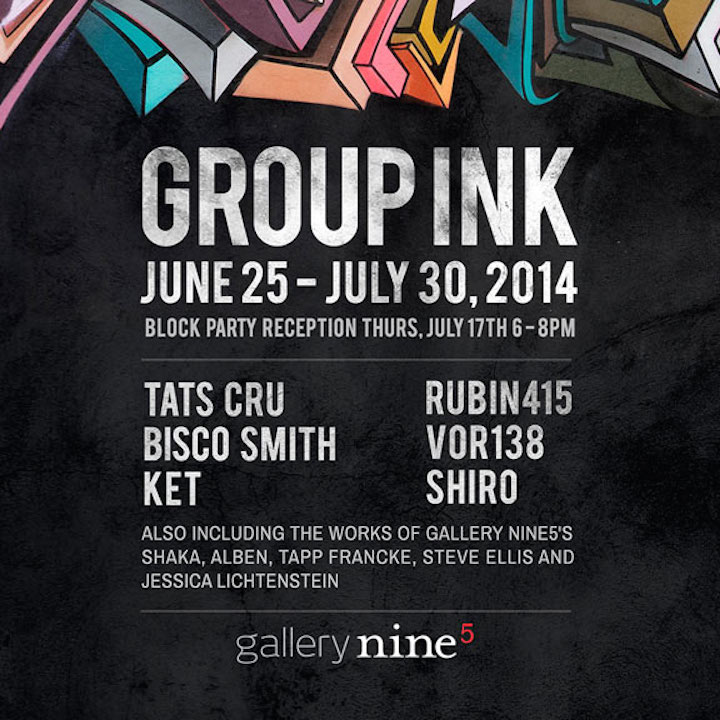

How do you feel about the movement of graffiti and street art into galleries?

I think it’s cool. I love to see my stuff hanging on walls, and when someone asks me to be in a show, I feel honored.

What about the corporate world? How do you feel about its engagement with graffiti and street art?

I have no problem with it. If the corporate bank writes me a check, I’ll cash it.

Is there anyone in particular you would like to collaborate with?

I would like to collaborate more with Eric Orr.

How do you feel about the role of the Internet in all of this?

The Internet is useful. It works for me.

Do you have a formal art education?

Yes I have a Masters Degree in Illustration from FIT.

Did this degree benefit you?

Yes, I now know my worth.

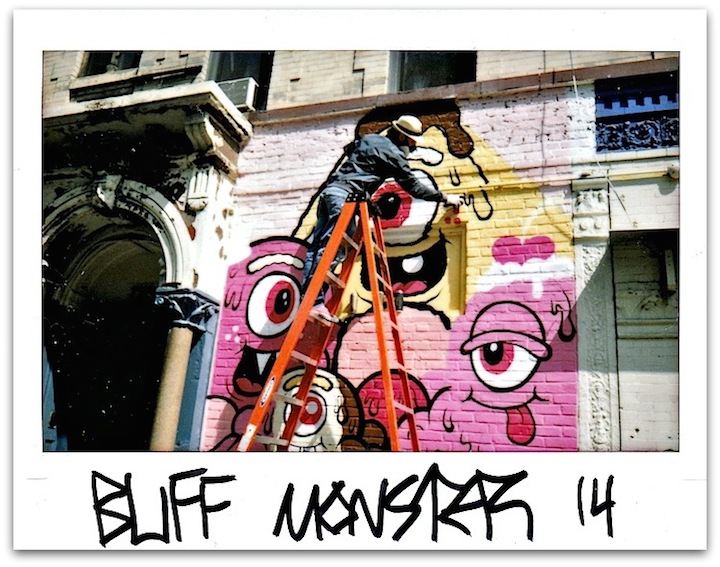

How would you describe your ideal working environment?

Outdoors, Florida-type weather and a generous paint sponsor.

What inspires you these days?

I’m inspired by the life I live and by the students I teach.

Are there any particular cultures that have influenced you?

The human culture.

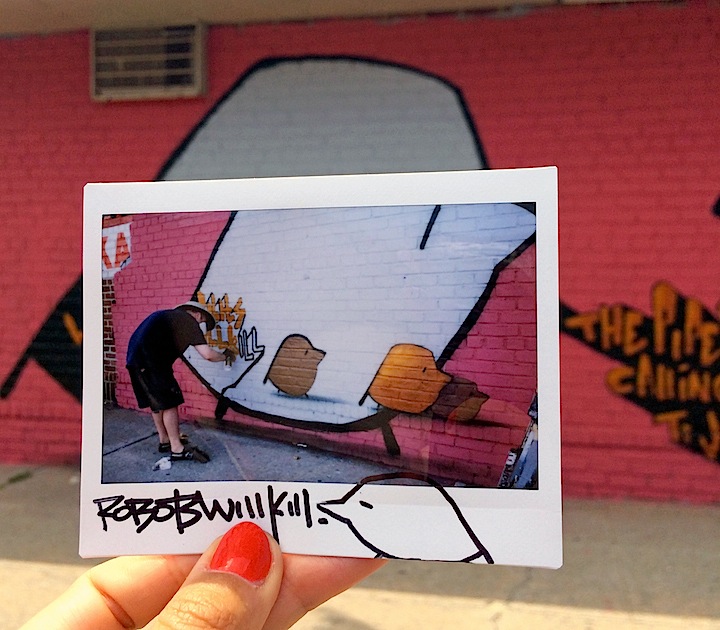

Do you work with a sketch in hand or just let it flow?

I work with a rough sketch, but I never have colors in it. This prevents me from becoming a slave to my reference, and it allows my creative mojo to experiment freely.

Are you generally satisfied with your finished piece?

Never.

How has your work evolved through the years?

My work keeps evolving and changing because I allow myself to experiment. I don’t like being stuck in one particular mode. That bores me.

What do you see as the role of the artist in society?

To give back… to share a gift that we artists have with others.

How do you feel about the photographers in the scene?

I think they’re helpful, but they should share any profits they make with the artists whose works they photograph.

What’s ahead?

I hope to be still doing what I’m doing while advancing my skills. I hope never to lose my passion.

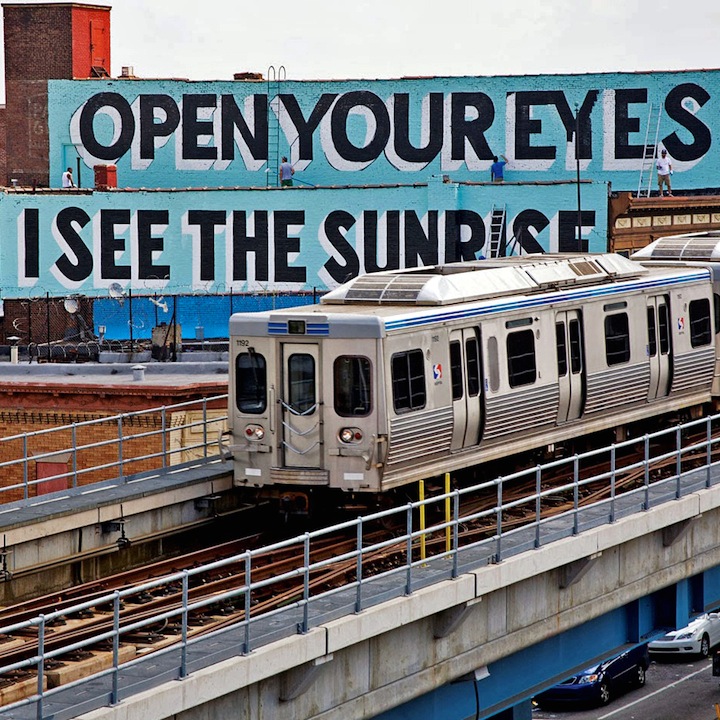

Interview by Lois Stavsky; photos 1, 2 and 8 (collaboration with Kid Lew) by Sienide; 3, 4 and 7 (on canvas) by Lois Stavsky; 5 (collaboration with Eric Orr) and 6 by Lenny Collado

{ 4 comments }