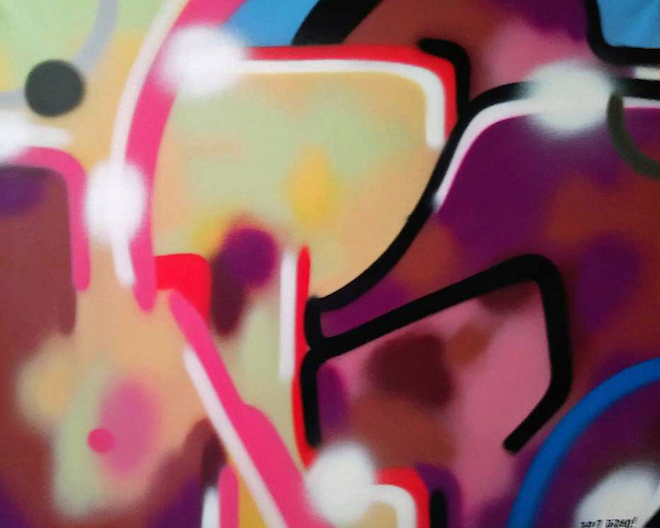

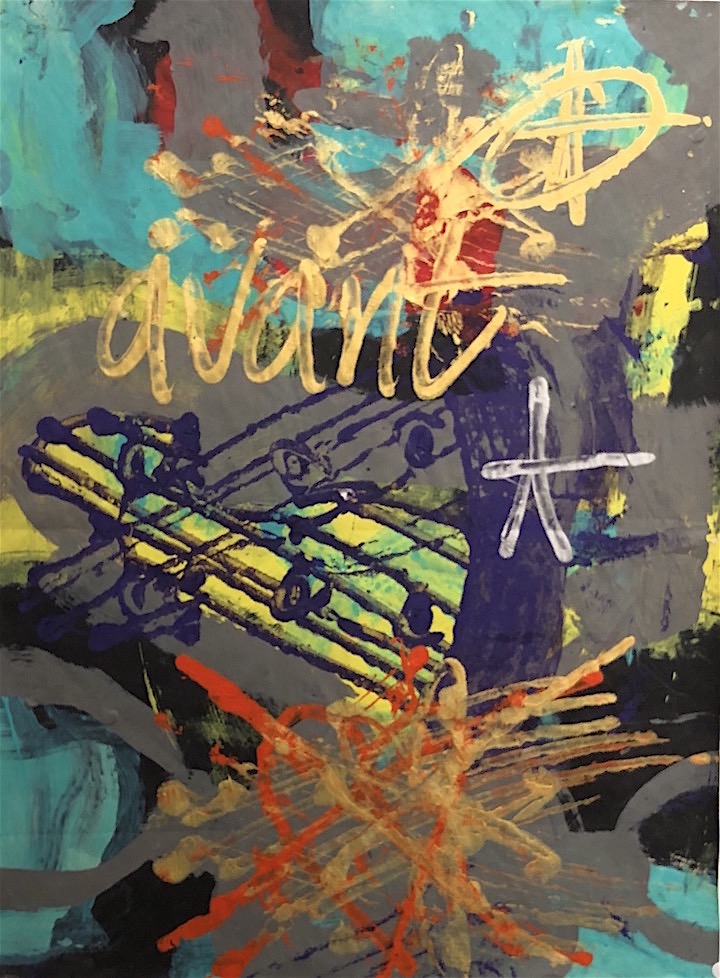

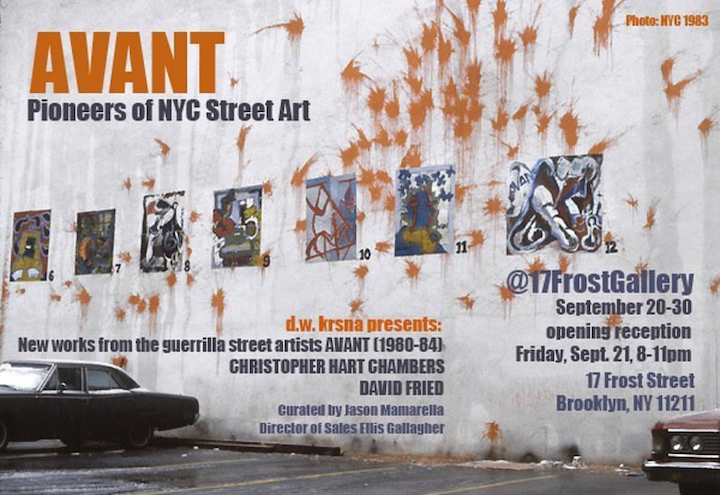

A member of Avant, the first artist group in NYC to use the street as an exhibition space for works that were created in the studio on paper, Christopher Hart Chambers, along with David Fried, will be exhibiting a selection of his artworks for ten days beginning this Friday at 17 Frost Gallery

StreetArtNYC contributor Lenny Collado aka BK Lenny recently had the opportunity to interview the legendary artist.

When did you first start drawing?

From the moment I could hold a crayon in my hand. I was about one or two.

What are some of your earliest art memories?

I remember when I was in the 4th grade, we were asked to draw a figure of a tree. I drew the tree. We were told not to color it. I colored it anyway – only to be told that I’d ruined it. I could never follow assignments; I always did my own thing. I also have memories of copying from baseball cards, making pencil sketches of baseball players. I remember, too, going to a museum and seeing all these grey wooden boxes with soda cans and wrappers. I had a piece of garbage with me, and I threw it in. Suddenly, all the guards raced at me. I didn’t get it. I was 11 at the time.

What about cultural influences? Any particular ones?

Jimi Hendrix — his music and visual projections. I give him major props because Hendrix rode a wave, divorcing himself from being a creator. When he was on, he was not really there. When the magic happens, the ego isn’t really there. The art takes on a life of its own.

What did your family think about what you were doing? Were they supportive?

My mother used to ask me, “Have you considered having a career?” I‘d say, “I have a career!” She never understood, and she never hung any one of my pieces. She didn’t like my stuff. My father, however, had pieces hanging from the floor to the ceiling.

How important is the viewer’s response to your work?

I like people. But I don’t think their opinion would actively make me change a piece. While creating, I really don’t want to hear what others think. Afterwards, I’ll listen.

Are you generally satisfied with your art work?

I never ditch a piece; I put it aside and keep at it. When they’re good, it’s like, I didn’t do it. I’m a conduit. I’m like, “Wow, where did that come from?”

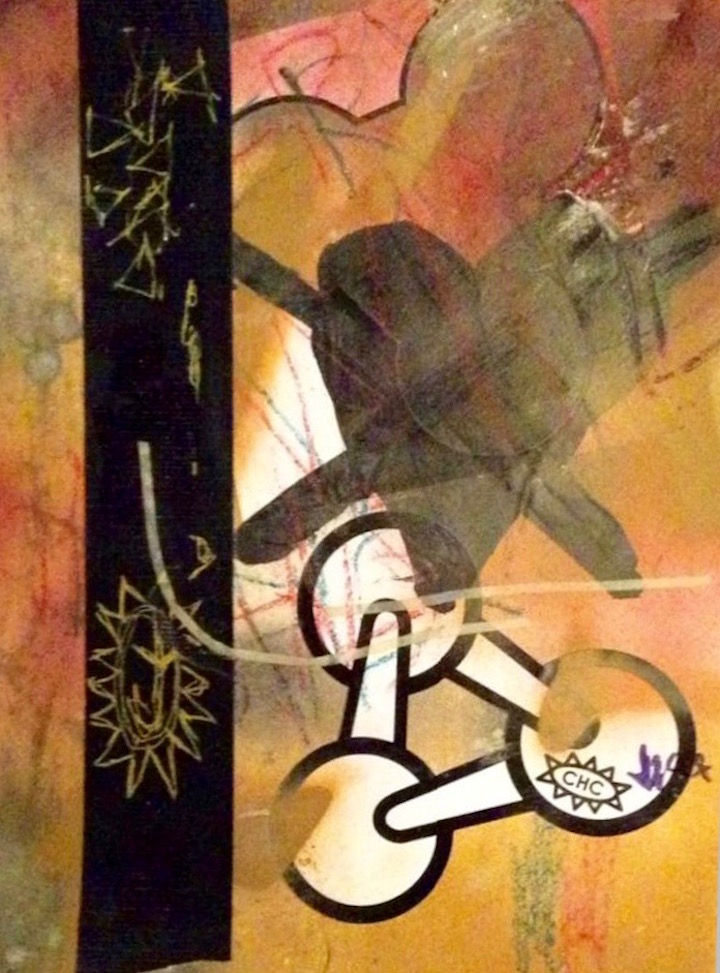

Have you a favorite medium?

Automotive paints.

How long do you generally spend on a piece?

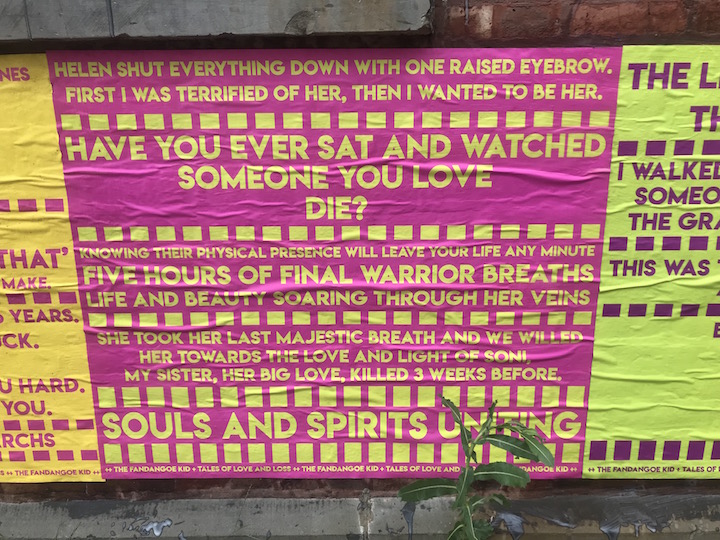

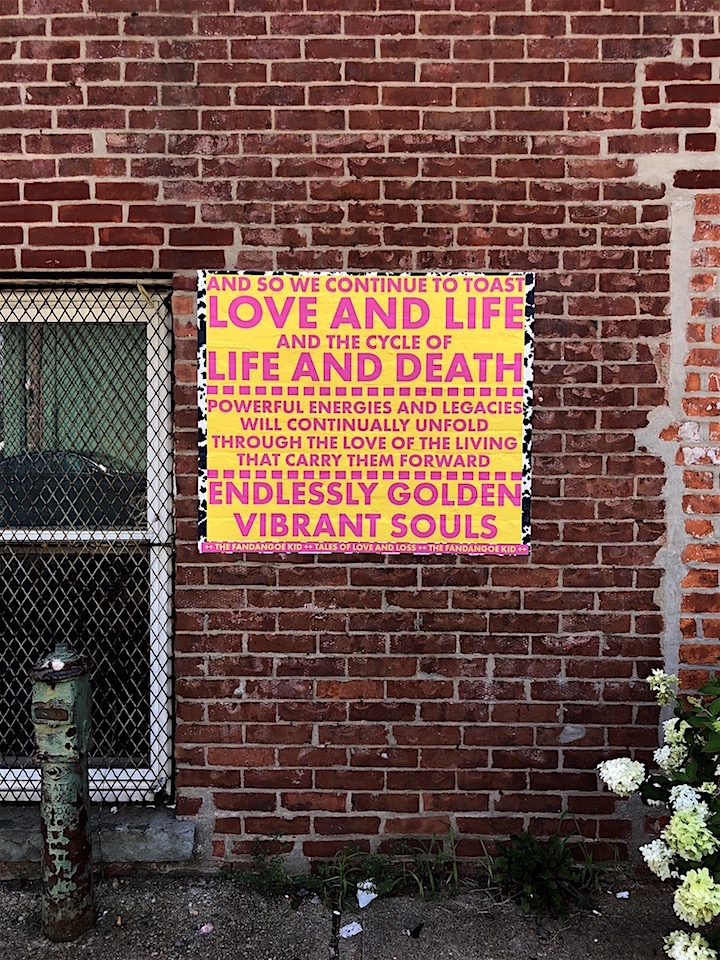

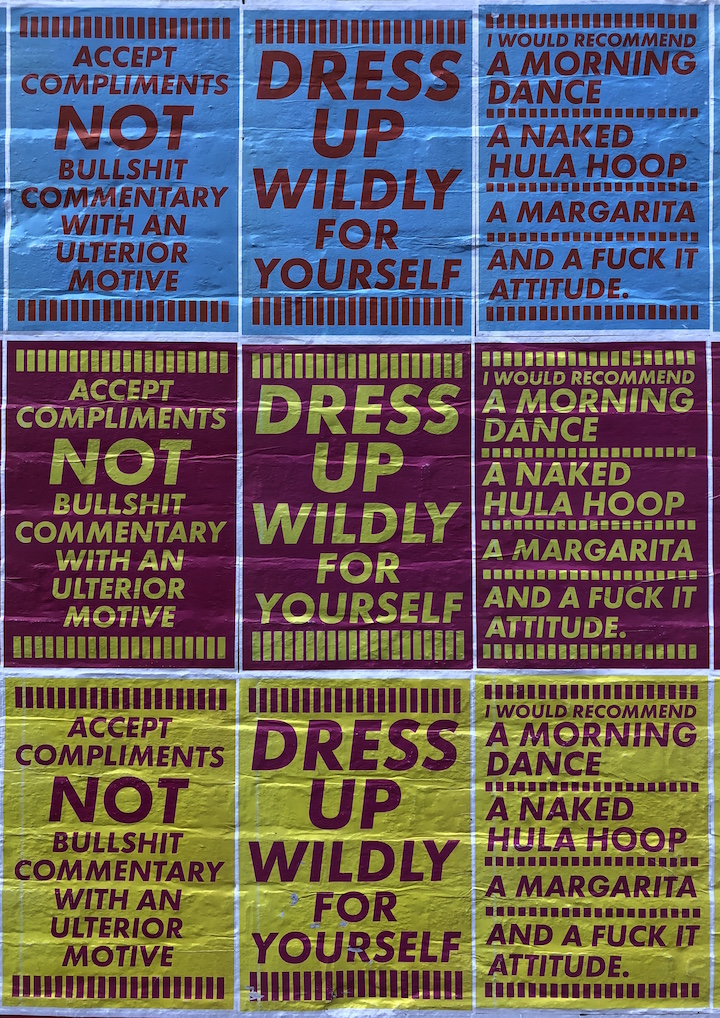

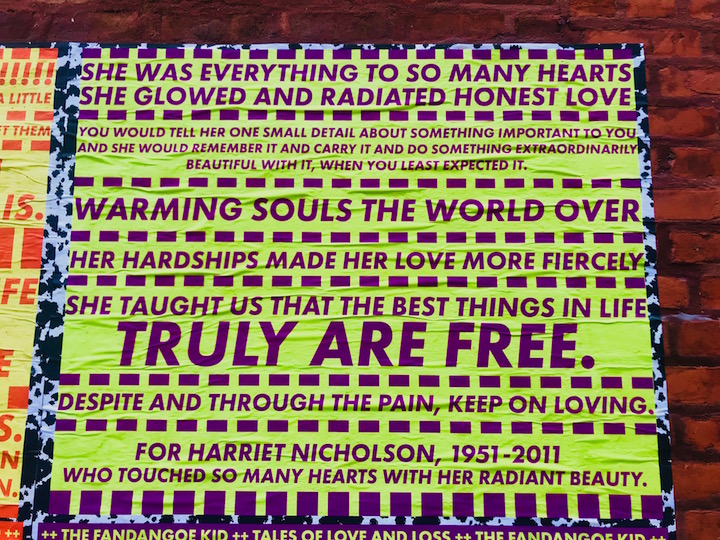

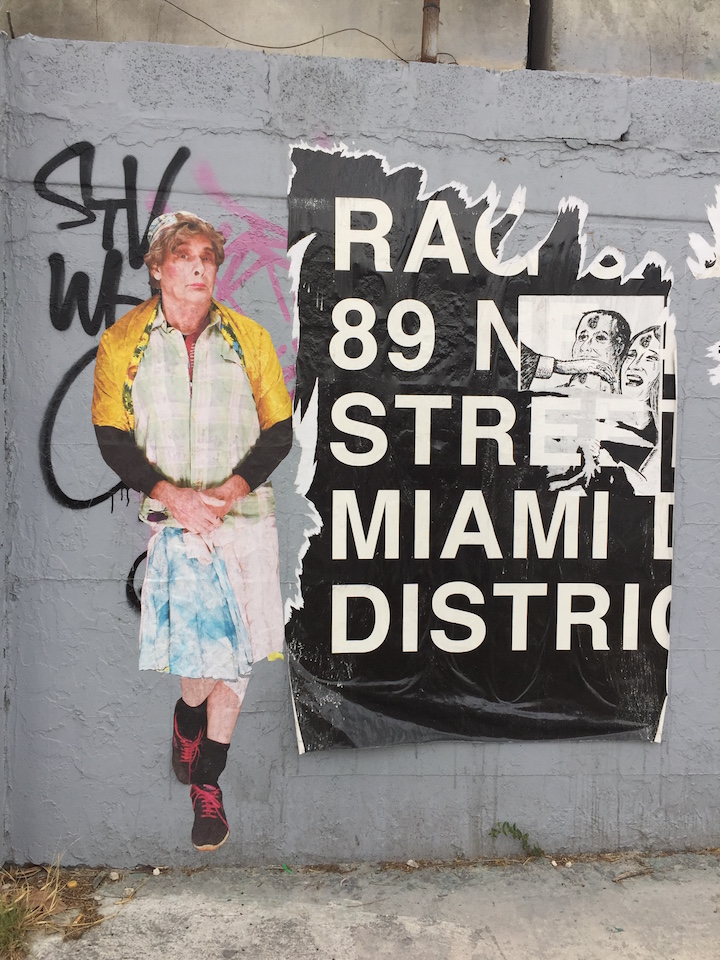

Impossible to answer. Several years. I don’t think I’ve ever effectively finished something in less than thirty seconds. My posters take about four days and I do 20 at a time.

What percentage of your time is dedicated to your art?

All of it! Even if I’m watching TV or sipping iced tea, it’s all part of it.

Do you have a favorite place to work?

I’ve always liked my studio. I’ve always lived in my studio.

How has your art evolved throughout the years?

It was simplistic at first. I’ve gotten better. When graffiti first hit, I guess I was still holding back. But then I started to feel like a fool. So, I said, “Just go for what you want now. Just do it!” That was about ’77. And since, I’ve explored several different mediums.

You were one of the earliest folks to impact the street art scene. Can you tell us something about that?

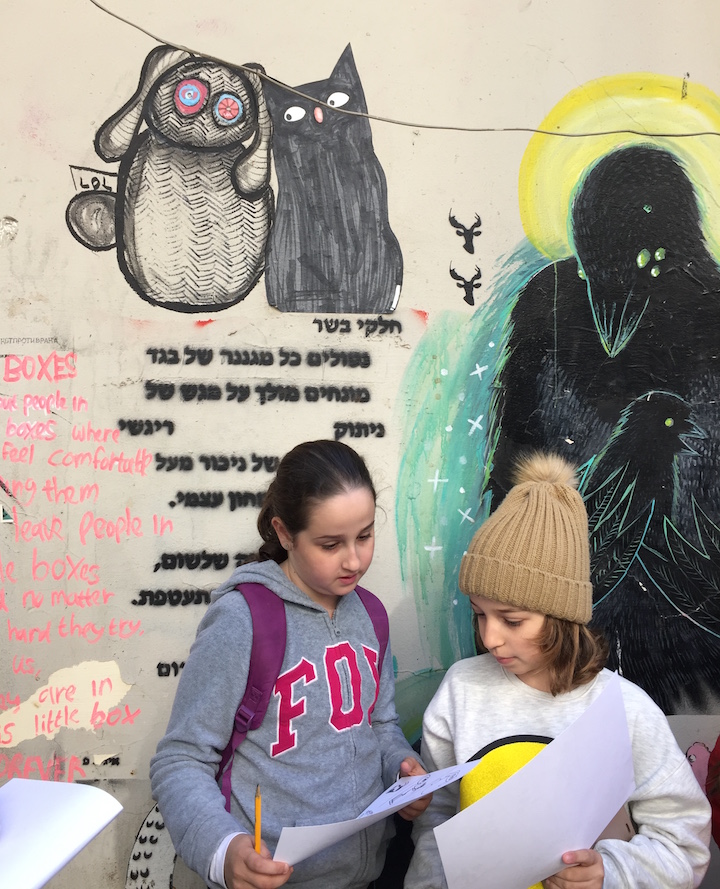

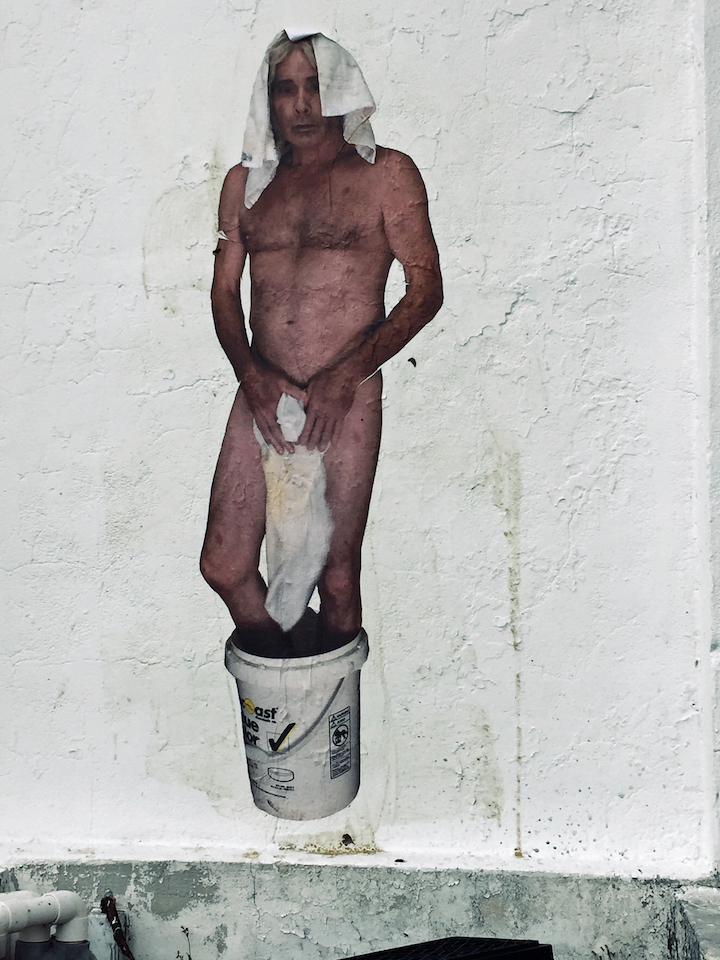

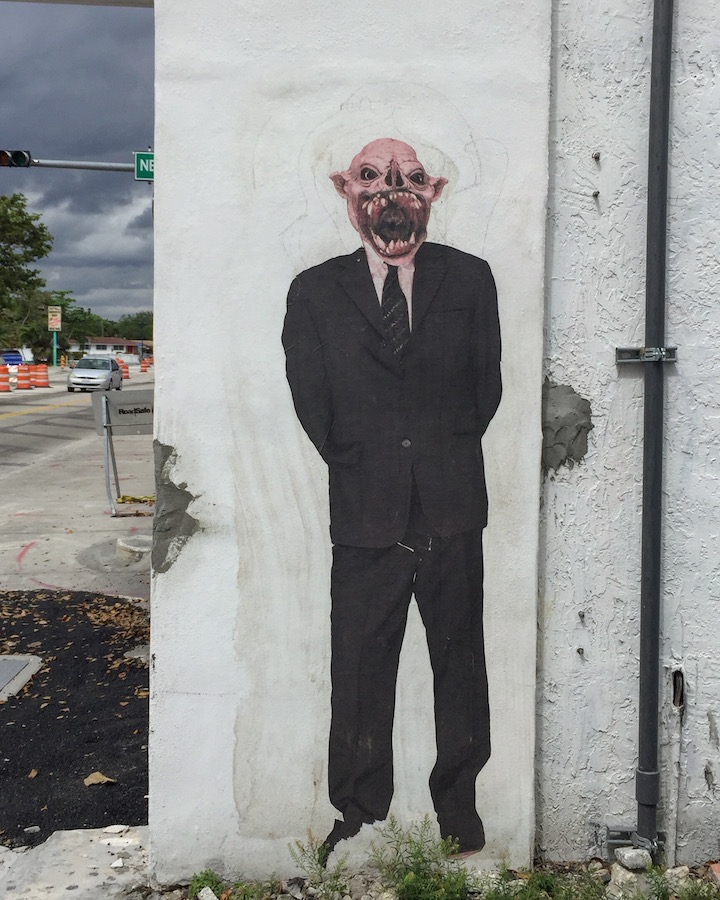

We were all about going on a campaign and using the street as an alternative space. We were in revolt against the galleries and the commodification of art. That was Avant. There was a strategy to the whole thing. When the street kids were going to the galleries, we were bringing the studio to the street. We were like a rock band, hitting as many venues as we could. We used paste-ups and paint to put up art on the street. The late painter and poet Rene Ricard called us “the enemy,” because of what we represented. We were on a mission.

Who were Avant’s inspirations back them?

We were largely inspired by Al Diaz and Jean-Michel Basquiat. SAMO© was a phenomenon, as it captured people throughout the city.

What is your main source of income these days?

Selling art, selling stories, and writing about other artists.

What do you see as the role of the artist in society?

He’s a priest or a cobbler with a compulsion, feathering the nest.

You’ve exhibited in dozens of venues from alternative sites to museums.

Yes! Among them were 51X Gallery, MoMA PS1, A.S.A.G.E. Gallery, Nassau County Museum of Art and Causey Contemporary. And my next exhibit opens this Friday, September 21 at 17 Frost Gallery, where I will be showing along with David Fried. in an exhibit presented by d.w. krsna.

Good luck! We are looking forward to that!

Interview by Lenny Collado; all photos, courtesy of the artist, selected by Tara Murray; and special thanks to 17 Frost Creative Director Javier Hernandez-Miyares

Note: Hailed in a range of media from WideWalls to the Huffington Post to the New York Times, our Street Art NYC App is now available for Android devices here.

{ 0 comments }