Aired last year in Italy, Sky Art’s underground documentary hit Graffiti A New York brilliantly chronicles the history of graffiti in NYC focusing on several key figures in the scene. After viewing the documentary, we had the opportunity to pose some questions to its producer and director Francesco Mazza.

You grew up in Italy. What spurred your interest in NYC graffiti? And how were you first introduced to its culture?

In the early 90’s a number of original graffiti writers from the Bronx moved to Italy looking to recover — thanks to the good weather and the healthy food — from the “crazy 80’s” in New York. They, maybe, needed what we now think of as a “detox” after the tumult. At the time, graffiti writing had already come to the European consciousness through the movie Style Wars and the book Subway Art, but because of the influence of these newly migrated Masters, Italy, unlike the rest of Europe, developed a graffiti style akin to that of New York City’s. It was the kind of style created by Phase 2, who moved to Italy himself, back in the 70’s. The walls of my neighborhood, Milano Lambrate, in the early 90’s looked exactly like those in the Bronx during the 70’s and the 80’s.

To us kids playing soccer in the street, those wall paintings were a sort of a mystery, and kids love mysteries. So, out of curiosity, we started asking questions to the older guys, and we all got involved. From that point on, graffiti became an essential part of our lives — in our neighborhoods and in our identities as individuals.

What made you decide to produce a film on the topic?

Having lived in New York for three years already, I was looking for a way to show the city to an Italian audience from a fresh and original perspective. I asked myself, “What do I know best?” The answer was clear: graffiti. I figured that behind the history of the graffiti movement, there was the history of the city itself. Really, graffiti writing could flourish only because of the terrible financial situation of New York during the 70’s. I always found it fascinating that all the crime and pain and blood of the 70’s spawned, at least, the most vibrant art movement the world has ever seen.

How long did the process take — from its conception to its completion?

The film itself took about a year to be made, but there are some elements of the history that I’d still like to add. I’m hoping for the opportunity to re-shoot some parts and add additional ones for a US release. I’m searching for funding right now. As great as it was to bring this to the Italian market, it has become clear to me that the documentary was the kind of record of a movement that deserves to be a part of the American canon, as well. It’s about NYC. It documents the scene decade by decade. It’s really important to find a way to bring this history “home.” Hopefully, I’ll find the financial backers; and due to the nature of the film, I’d love to partner with a museum, if possible.

How did you decide which artists to include?

“Graffiti writer” is a label. When you look beyond the label, there is literally everything. Artists, addicts, entrepreneurs, fools, poets, murderers; you name it, I saw it. Right off the bat, you have to understand that you won’t be able to get close to everybody if you want to stay somewhat safe. It’s also very hard to gauge the importance of the single artist. Is a graffiti artist important because he had or has a great style? Cool, but what if the said writer has done only a couple of hits and nobody in the community cared about him? And what if you focus on the quantity, but then the style of that writer — whose name was everywhere — literally sucked?

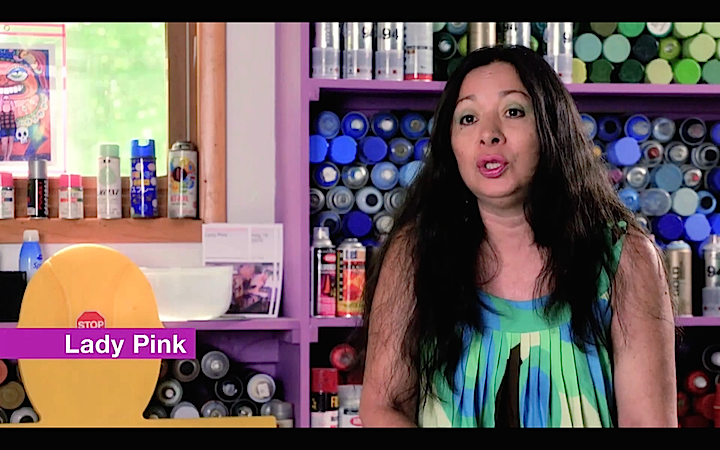

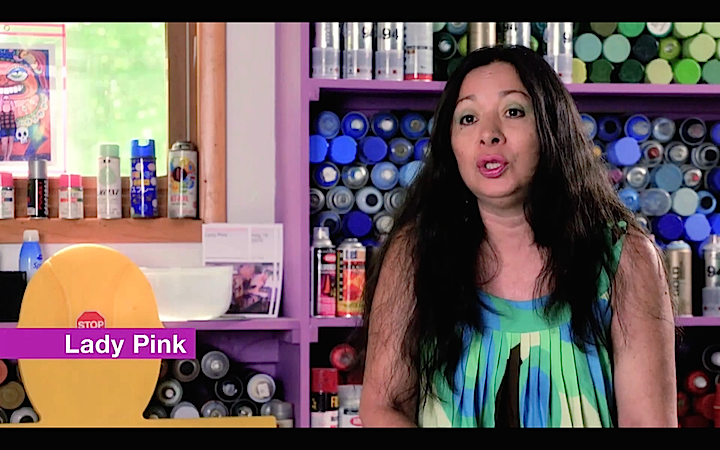

There was a balancing act. I, of course, chose artists with historical importance, but I also reached out to the writers that I like and that inspired me when I was a kid. Fortunately, most of them were willing to help me with the project. I also felt strongly about making sure women were represented in the film. They were absolutely a part of the movement, but sometimes when history chronicles events, women don’t always get the due they deserve in the record. It was important to me to not fall into that trap as a director.

How did the artists respond to you?

Some of them were skeptical at the beginning, and they were absolutely right. When mainstream media talks about graffiti writing, they tend to create confusion. If we consider the art world, I think that after the 19th century, nobody considered an artist as someone who can only “make something look pretty.” Nobody thinks that Pollock, so to say, was an amazing artist because he could simply “make a canvas look pretty”; there was a complexity that was beyond — or sometimes even consciously lacking — beauty. For some reason, all around the world, when media, or institutions, or public opinion deal with graffiti writers, they consider the graffiti writers’ work just on their ability to “decorate” a wall in a happy, colorful way. To me, and I think to all graffiti writers, there is, indeed, decoration. Maybe beautiful, wonderful decoration, but graffiti writing is also something else. Graffiti writing points right to the contradiction of contemporary society where we all matter. We all pay taxes and have the right to vote — but, at the same time, to what degree do we really matter to the machine? I think it’s a question everyone asks. As a result, millions of individuals decide to express their identity, their presence in the world by writing on a wall, consciously facing the consequences of their deeds.

When I walk in my Crown Heights neighborhood in Brooklyn and I see a portrait of a dragon on a shutter, I think, nice illustration, but nothing beyond that. When I see a rough tag on a wall, I don’t say, “Look at that! So pretty!” but I think about a guy or girl that, despite the risk of getting busted and sentenced to two years of prison, decided to face the challenge and put his freedom at jeopardy to have me see his name. Now, what is more interesting, from a social/cultural point of view? The fellow who copies an illustration of a dragon and gets paid for that, or the one who takes the risk for free to screw up his life forever just to have one individual out of one hundred thousand reading his name? I personally have no doubt about which is both more interesting and matters more. So, the graffiti writers I contacted were really scared that I was another guy from the media industry with no grasp at all of the roots and the meaning of the movement. It took me a lot of time and efforts to gain their trust, but once they realized what I was talking about, they were really cooperative and with some of them I built great friendships.

What were some of the challenges you faced in producing the film?

I served as writer, director, and executive producer. The network, Sky Art, gave me a budget, and I was free to manage it however I liked. But that was hard, because as a director, I always wanted more — more days of shooting, more footage, more writers to interview — but as an executive, I had to put some limits. It was like being two different people at once. Now that I can look back, I better understand the limitations I had and their effects on me. And an American alternative presentation — that wasn’t able to be made at the time — is something important to pursue going forward, as much to “do right” by NYC.

Who was/is your target audience?

The original documentary targets an Italian audience who is fascinated with New York but doesn’t really have a knowledge of it, as well as everybody else who wants to know, once and for all, the real history of one of the most relevant artistic, cultural and, to a certain extent, political movements of the 20th century. Now I need to broaden the reach beyond Italy.

Will New Yorkers have the opportunity to view it?

Unfortunately, as of now, they don’t, and that’s a travesty. That’s where my fight is now — finding a means to change that. Everything about this movie is New York City. The residents need this film. It needs to be a contribution to their historical record. Hopefully, I’ll find the funding for what is really a “preservation” project. People aren’t around forever. The interviews with important artists in Graffiti A New York, all in English, need to come “home.”

I certainly agree! Graffiti A New York is not only a passionate homage to the roots of graffiti, but an essential visual and spoken record of a significant NYC era. What’s ahead for you? Can we expect any more films on the topic of street art or graffiti?

Currently I’m working on a project for the Discovery Channel for which I hope to be able to announce details soon. Later this year I’m doing a documentary on Stewart Brand and the Whole Earth Catalogue that I’m very excited about. This fall I’ll be shooting a short project in New York again. I’m also continuing to show Frankie: Italian Roulette, my short fictional film from last year, at festivals across the US. Next up for Frankie is the Crossroads Festival in Jackson, MI on April 2. Even Frankie is about life in NYC and fighting to stay there, so — going forward — it’s no surprise that I’ll, of course, continue to focus on the themes present in Graffiti A New York: art, actions of consequence, social responsibility of both the system and the individual, and, of course, the city of New York itself. And, fingers crossed, we can make the US adaptation of Graffiti A New York. That really must happen.

The questions for this interview were formulated by Lois Stavsky and Tara Murray after viewing the European market release Graffiti A New York.

Note: Hailed in a range of media from the Huffington Post to the New York Times, our Street Art NYC App is now available for Android devices here.